Free Your Mind Part 3 - The Automatic Imagination Model

This is the third part of the Free Your Mind article about our work at Head Hacking Research. The first two parts described the popular and academic models of hypnosis, from Estabrooks to Wagstaff. In this part, I will review some more scientific data and build the case for The Automatic Imagination Model. Please read parts 1 and 2 first to familiarise yourself with the approach I've taken and understand the context from which this was written. This part is based on my talk at change | phenomena, the hypnotism conference, 2012, What do we know about Hypnosis?:Direct link to video on YouTube.

I feel it worth pointing out that when Anthony and I first had the insight that led to the Automatic Imagination Model, it was more of a flippant joke than anything serious; we were travelling back from a course, summarising to each other the bits of the scientific research we had read. At that time we had some faith in the Human Givens model of hypnosis (see part 1) which was essentially a special process model; we had relieved ourselves of state and depth, but were still expecting hypnosis to be something akin to a shift in processing, from 'normal' to 'hypnotised'. To conclude that it was all possible with just the imagination seemed ludicrous, but that was what the science appeared to suggest. We arrived at Anthony's house and did some tests - neither of us are good subjects but I achieved amnesia and Anthony hallucinated, both with the sense of involuntariness that accompanies hypnotic experiences. Wondering whether our success was more related to our increased expectations than anything revolutionary, I described the process to Marcus Lewis over the telephone; that night he tested it on someone who previously did not respond to suggestions or inductions, and got the guy to experience amnesia and hallucinate, without an induction, in under two minutes. At that point we all decided that this was something that needed further investigation.

What do we Want?

As hypnotists, we are interested in the subjective experience that our subjects are having; the sensation of involuntariness or automaticity, that the behaviour is happening by itself and that they (their conscious awareness) is just a mere observer. If you're performing with hypnosis, then you want the subject to be hypnotised, not acting, because no one can act as well as a hypnotised subject. If you're a hypnotherapist, then you want the subject to be hypnotised, not pretending, because if your therapy model relies on the hypnosis then it may not work if the client is pretending. What we want to achieve in our subjects is this sense of involuntariness.Imagination

John F. Kihlstrom, a social cognitive theorist, stated (Kihlstrom, 2008): "Hypnotic experiences take place in the realm of imagination - there isn't really a balloon lifting up the subject's hand, or glue holding the subject's hands together, or a loudspeaker on the wall; nor does the age-regressed subject grow smaller in the chair. Nevertheless, the relationship between hypnosis and mental imagery is rather vexed. For example, hypnotizable individuals have no better mental imagery abilities that the rest of us." He notes two clear things: first is that hypnosis relies on the use of the imagination; and second is that subjects that respond well to suggestion generally have no better skills of imagination than those that do not. This is quite significant because it means that what you see when you imagine a rat, for example, is the same as what you would literally see if you were acting on a suggestion that you could see a rat; obviously, they would feel different because when you simply imagine the rat it doesn't feel real at all. The difference isn't in the quality of the imagining, but how it is perceived.If hypnosis causes subjects to imagine, then what is it that they are imagining? Traditionally, suggestions have contained what academics refer to as goal-directed fantasies (GDFs); these are instructions to imagine that helium balloons are lifting the arm or glue is sticking it down. If the goal of the suggestion is arm levitation, then a goal-directed fantasy would be an imagined scenario that would be likely to cause the goal to occur, such as hundreds of bright red helium balloons attached to your wrist, pulling it upwards. If the goal is a stuck hand, then a goal-directed fantasy could be imagined glue sticking the hand down.

GDFs are also referred to as means imagery, to distinguish them from goal imagery. If the goal of the suggestion is arm levitation, then the goal imagery would be imagining the arm lifting up; if the goal is a stuck hand, the goal imagery would be imagining that the hand is stuck and cannot lift. Means imagery (GDFs) and goal imagery are quite different and it is important to appreciate the difference. Means imagery is indirect, creative and expressive, while goal imagery is direct and specific.

Gail Comey and Irving Kirsch investigated whether instructions to imagine goal-directed fantasies (means imagery) affected how well suggestions were taken (Gail Comey and Irving Kirsch, 1999). They took 259 subjects who had no prior experience with hypnosis and randomly divided them into two groups. One group received the standard Carleton University Responsiveness to Suggestion Scale (CURSS) and the other group received a modified version of the CURSS, with all instructions to imagine GDFs taken out and replaced with repetitions of the remaining suggestions. For example, "Imagine that your arm is like a balloon. Imagine that air is being pumped into it making it feel lighter and lighter," was replaced with, "lighter and lighter. ..the arm is becoming more and more light, and is rising, rising ...moving up ...higher and higher."

Each subject scored their objective behaviour (CURSS:O), their subjective sensation (CURSS:S), whether the effect of the suggestion was experienced as being involuntary, whether they believed in the reality of the suggested situation, whether they engaged in goal imagery, whether they intentionally engaged in GDFs, and finally whether they noticed any spontaneously occurring GDFs. Subjects were also scored for their "passive responding", which was an indication of whether they remained passive and didn't engage in any strategies at all, i.e. "Did not report intentional behaviors of imagery."

The results revealed three striking observations. The first was that, "Passive responding was negatively correlated with subjective response." This means that the subjects that remained passive, didn't engage in any intentional behaviours and didn't imagine anything relating to the suggestion, were more likely to not respond to suggestions, than subjects that did engage in some way. This indicates that, in general, subjects have to do things in order for hypnosis to occur; passively waiting for it to happen is not a good strategy. If you are telling your subjects or clients that they can just relax and let it occur, then you are probably reducing your effectiveness. The subjects that you fail to hypnotise are not necessarily resisting your suggestions; they might simply be waiting for hypnosis to happen which, as long as all they do is wait, it appears it will not. (Given that they think that their job is waiting for hypnosis to happen, further instructions to "Let go" are unlikely to be understood as any different to what they are already doing. It is easy to see how this situation could be misconstrued as "resistant" by a hypnotist, even though the subject is willing and cooperative.)

The second striking observation was that, "The only GDFs that are positively associated with successful responding are those that are judged to be nonvolitional." This means that subjects that reported spontaneously imagining GDFs (i.e. did not feel that they were intentionally imagining them) responded better to suggestions than those that did not. Spontaneously occurring GDFs were rare, however. It also means that subjects that intentionally imagined GDFs (i.e. volitionally) did not respond better to suggestion; in fact, they responded worse than those that did not intentionally imagine GDFs! Intentionally imagining GDFs was negatively correlated with response.

The group that had been given the modified version of the CURSS (with the instructions to imagine GDFs removed) scored higher for objective behaviour, subjective sensation, involuntariness and, to a lesser significance, the perceived reality of the suggested situations, than did the group that received the standard CURSS, with the instructions to imagine GDFs. This shows that instructing subjects to imagine GDFs - the balloons of an arm levitation or the glue of a hand stick - will, in general, reduce the effectiveness of the suggestions.

Comey and Kirsch suggested that one reason why intentionally imagining GDFs reduces response might be because the effort involved in intentionally imagining GDFs distracts or detracts from whatever effort is required for the suggestion to succeed. In other words, doing something that isn't involved in making the suggestion work (imagining the GDFs) reduces the brain power available to attend to the task of making the suggestion work (whatever that is). This turns the typical format of suggestion on its head - asking subjects to imagine GDFs actually reduces the effect of suggestions, whereas the rare, but spontaneously occurring GDFs may simply be an occasional effect of suggestion rather than a mechanism that is significant in their working.

If that wasn't enough, the third striking observation was that, "Intentional use of goal imagery was very common and was significantly associated with subjective responses to suggestion," and, "Our data indicate that intentional goal imagery is a modal strategy even for very difficult responses (i.e., auditory and visual hallucinations)." Comey and Kirsch sorted the data to reveal which strategies the successful responders were using, broken down by suggestion. Successful response was judged as passing the behavioural criteria of the suggestion. In all suggestions other than amnesia (in which they asked if the subject "Tried to forget" rather than whether they imagined they couldn't remember), successful responders reported engaging in goal imagery (imagining the goal of the suggestion), on average, in 73% of cases, and this was reasonably consistent regardless of suggestion: arm rising was 79% and hallucinated kitten was 77%.

Imagining the goal of the suggestion is correlated with feeling the effects of the suggestion. This means that imagining the goal of the suggestion is a good strategy for succeeding at experiencing suggestions. It also works equally well for all phenomena, rather than only working for a particular class of phenomena, meaning that is a good strategy in general, rather than only being a good strategy for, say, ideomotor suggestions.

It has long been known that imagining an action can cause its effect (James, 1890, and Arnold, 1946, ideomotor hypothesis, cited in Comey and Kirsch, 1999) and most of us should be able to experience this. Chevreul's pendulum is a good example; if you take a pendulum (about 30cm of string with a metal washer tied to the end) and hold the free end with your fingertips, resting your elbow on a table and allowing the pendulum to hang freely over the table, then if you imagine that it will move in a straight line backwards and forwards, then it will begin to do so; equally, if you then stop imagining that and imagine instead that it will move around in a circle, then it will change and follow your newly imagined scenario. You should be aware of imagining the desired action, but unaware of the tiny muscle movements required to make it happen. Through imagination, the mind creates the physical effect without the awareness of moving the muscles.

A good question could therefore be, is everyday imagination enough? The pendulum task requires constant attention in order to experience its effects - if you stop imagining or get distracted then it is likely to stop - and therefore doesn't really feel involuntary, even if we do temporarily experience a sense of dissociation from the actual muscle movements. The Raz et al paper (Raz et al, 2006), referred to in part 2, shows that suggestion alone (without an induction) can reduce the Stroop effect. Is this possible with just the imagination? The following video shows Marcus Lewis being tattooed under hypnosis without any pain, awareness or bleeding. Is that possible with just imagination?

Direct link to video on YouTube.

It may be possible to simply imagine these effects and cause them to happen, but, as with the pendulum, the process would require effort and attention and would not feel involuntary. Clearly something else is required beyond everyday imagination, and that is the sense of automaticity or involuntariness.

Quick recap

At this point I think it is worthwhile to quickly recap what we know.Imagination:

- Goal imagery is significantly associated with subjective responses to suggestion (Comey and Kirsch, 1999).

- Goal imagery can cause behavioural responses akin to hypnotic responses but without the required sense of involuntariness (James, 1890, and Arnold, 1946, ideomotor hypothesis).

- Highly hypnotisable subjects do not have greater skills of imagination than others (Kihlstrom, 2008).

- Therefore, goal imagery is a good strategy for succeeding at taking suggestions, but it isn't sufficient as the results of everyday imagination do not feel involuntary.

Automaticity:

- All thoughts and behaviour are automatically generated, some of which we become aware of and to which we usually ascribe intention (Kirsch and Lynn, 1997). (See part 2 for more discussion.)

- Hypnotic responses are defined by their subjective sensation of automaticity or involuntariness, because they lack the knowledge or feeling of intention. (Kirsch and Lynn, 1997).

We are automatons, presented with an on-going illusion of consciousness and agency. No matter how much it feels like you have conscious control, you don't - that's just an illusion created by your automatic brain. Altering this illusion causes actions to be perceived as happening automatically or involuntarily. While we are imagining the effect of the suggestion, it is not that we need to create the sensation of involuntariness - for everything is actually involuntary - it is that we need to remove the sensation of intention that has been ascribed to the action.

The Automatic Brain

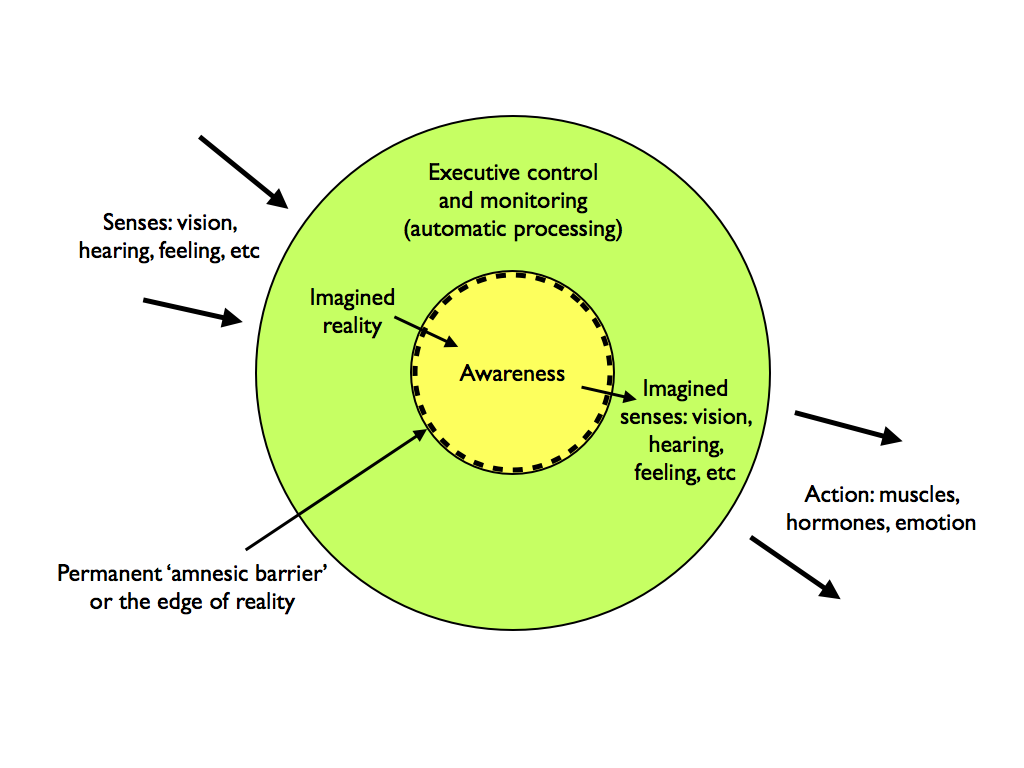

This is our simple model of the automatic brain. In pictorial form, the green/yellow part is essentially the brain; and the white part is the body. Awareness, the yellow part, is generated automatically by the brain.

The brain senses the environment through our senses; generates an imagined reality based on what it already knew and what it has sensed; generates awareness of this reality including the automatic thoughts about the reality; senses the effect of the awareness of the imagined reality, such as the imagined sights, sounds and sensations; and, combining the data with the real senses, produces action in the form of muscle movement, hormone production and emotions, by matching these 'inputs' to the most appropriate 'output'. This happens continuously and rapidly and, because our awareness only has access to the imagined reality, we are largely (completely?) unaware of it going on.

The permanent 'amnesic barrier' prevents us from accessing our actual thought processes and brain functions as these lie literally outside of our reality; instead we confabulate or guess at the reasons why we do or think certain things from the information available to us from within our imagined reality.

Automatic Imagination

The insight that Ant and I had, that I referred to in the opening of this part, was that if everyday imagination can create reality, other than the fact we know that we're imagining it, then we should be able to use the same mechanism (imagination) to create a reality in which we were unaware that we were imagining! In other words, use imagination to create the effect and then use imagination again to cover up the fact that we know that we're imagining the effect. This should result in us experiencing the effect as if it is real, while being unaware that we are imagining it, hence being unable to stop it, and experiencing the effect as occurring automatically.This can be tricky to convey, so I'll try again. If we imagine that our hand is stuck to the table, then while we continue to imagine that, we will be unable to lift our hand; we will know that we're imagining it, however, and can stop imagining it any time we want, in the blink of an eye, simply by needing our hand for something else. While we continue to imagine that it is stuck, though, it should remain stuck (based on the ideomotor hypothesis). If, while we're imagining that it is stuck, we also imagine that we are unaware of imagining that it is stuck, as if it has happened all by itself, then we should experience the stuck hand without knowing how it happened, and therefore no way of undoing it.

Exactly! That's a wacky idea to come up with, isn't it? Well it was initially a joke; it was a simple application of pseudo-logic to the evidence that we had become aware of. We didn't expect it to work; it was just a bit of fun. Even so, we ended up playing with the idea that evening and it worked for us. Neither of us had been particularly high responders before - we could both achieve arm levitation and I could get catalepsy, but little else - but that night I had amnesia for my name and Ant hallucinated his hand turning into a modelling balloon. I explained the process to Marcus on the phone the next day and he tested it with another known low responder and achieved the same classes of phenomena with him.

The format of these sessions resembled a normal conversation where the hypnotist simply asked a series of questions and gave clear instructions, and the subject remained awake and fully alert throughout. "Can you imagine that your hand is stuck to the table?" - "Can you continue to imagine that and also imagine that you're not aware that you're imagining that, like it's happening by itself?"

By assuming that the ideomotor effect can be generalised to include all phenomena, the same process can be used to achieve any hypnotic phenomena. The theory suggests that, as long as the subject can imagine the scenario (including it happening automatically), then all phenomena are equally as likely as each other. This can be seen in how Ant, Marcus and I all use slightly different approaches. I prefer to stick to the conversational, question style where I simply ask questions and modify what I'm asking them to imagine based on their answers; I start with a hand stick, then arm levitation with laughter, followed by amnesia. Marcus uses a similar structure but directly instructs the subject to imagine, rather than asking them if they can imagine; Marcus will often start with a hand stick and then go straight for amnesia although he also starts with amnesia on occasion. Anthony often sticks much more closely to the structure outlined in Reality is Plastic and The Trilby Connection, but with his language now laced with Automatic Imagination instructions; equally, though, he will just as often start with a visual hallucination and then go to other phenomena from there.

Our experiences with Automatic Imagination suggest that once subjects understand what is being asked of them, that they usually find it easy to do and are therefore surprised at the effect that they achieve. Once their imagination becomes automatic - that they are no longer aware that they are imagining the effect - they appear to be stumped for how the effect occurred and seemingly cannot undo it. We often liken it to disappearing down the rabbit hole so far that you cannot find your way out. It appears that subjects cannot connect their awareness of imagining that they're not aware that they're imagining (follow that?) with the effect that they have produced through their initial imagining. Whatever it is that they are imagining - dancing fairies, that everything in their pockets belongs to me, that they cannot remember their name - persists without any awareness of the effort or process that is producing it, nor how to stop it, causing the effects to be perceived as automatic and involuntary. Generally, audiences are surprised at how little we appear to do to cause these effects that mimic hypnotic phenomena in all characteristics.

Reminders of Reality

In some cases, the subject will imagine as requested but will be left with some knowledge that the effect is not real; we call these pieces of knowledge, 'reminders of reality'. With our eyes open (as many of our subjects experience the effects of AI), we have a lot of reminders of reality. Just seeing our hand would normally remind us that we have (the perception of) volition over it, that if we choose to move it, we can. In a classical hypnotic context, these reminders of reality would threaten our suggestions, potentially causing them to irrevocably fail. With AI, however, we can do things with these reminders that can remove their effect.First, however, I'd like to discuss higher-order thoughts (HOTs) and Cold Control Theory (Barnier et al, 2008). There is a theory that we have lower-order thoughts and higher-order thoughts. Lower-order thoughts are those that we are not aware of, that actually sense the environment and construct our awareness; higher-order thoughts are the thoughts that we become aware of, which include thoughts about our awareness.

Cold Control Theory is a theory of hypnosis based on the absence of HOTs (higher-order thoughts). Barnier et al stated, "Cold control is executive control without appropriate HOTs" and "Hypnotic responding does not involve changes to first-order representations (intentions can function as normal) but a change in a specific type of second-order representation - the awareness of intending." This implies that hypnosis causes a shift in the thoughts we have in awareness, rather than anything special happening in the rest of the brain. While this aligns with our ideas, cold control theory doesn't provide a mechanism for causing changes in the HOTs, other than that provided in suggestibility modification (such as the CSTP - see part 2).

Barnier et al stated, "The change involves avoiding accurate HOTs as well as entertaining inaccurate HOTs." If we apply this to reminders of reality, then we can see that all of our reminders must be HOTs, because they are in awareness (only lower-order thoughts are outside of awareness). Cold control theory is a manipulation of these HOTs in order to alter our awareness of our intentions. Applying the imagination ideas of AI, we simply ask the subject if they can imagine the same things again, but this time also imagine that their reminders will not be present, or that they will not notice them, or that they will not affect the process. This approach can be iterated for as many reminders as the subject becomes aware of, until no reminders remain and the effect then works.

Another way of attacking accurate but obstructive HOTs (reminders of reality), is to use emotion against them. The neuroscience suggests that our emotions affect the way we think (for a review see Dolcos et al, 2011). The Human Givens model suggests that high levels of emotion result in what they term 'black and white thinking'. This is where extreme levels of emotion causes extremities in thinking, with equally extreme emotional content. A phobic person in the presence of their phobic stimulus would be a good example: in that state of emotion all they want to do is end the situation and avoid the stimulus as quickly as possible, no matter how irrational that makes them appear. They might shriek while they do it too. The HOTs that drive their behaviour are extreme and specifically relevant to the perceived immediate danger.

While we could find no academic literature testing a link between levels of emotion and response to suggestion, we did find a study that showed that the admission of nitrous oxide increases response to suggestion (Whalley and Brooks, 2008). The authors could not rule out the possibility that the increase in response was due to the emotional effects of the drug, rather than a specific chemical effect, and suggested additional research. While reviewing the effect of other drugs on response to suggestion, they noted, "The fact that such a wide range of drugs with varying pharmacological properties have been demonstrated to affect suggestibility argues for a non-specific effect of drug upon suggestion," which could support the idea that the increase in response was due to a common drug effect, such as the presence of emotion caused by the psychological effects of the drugs, rather than the chemical compositions of the drugs themselves.

Our informal testing has shown that if subjects are emotional (excited or laughing, for example) then our results improve significantly; this is one reason why we usually aim to get our subjects laughing early on in our routines. We suggest that increased levels of emotion change the significance of HOTs, possibly making those with higher emotional value more significant to us and those of lower emotional value less so. In a hypnotic context, the HOT of "Hypnosis doesn't really exist or make any sense so this is unlikely to work" is quite rational and of lower emotional value, while the HOT of "What if this works?" has much higher emotional value as it could potentially lead to novel and challenging situations. Our suggestion is that when we are emotional, the "What if this works?" HOT becomes much more prominent and the "this won't work" HOT fades into obscurity. The result is similar to imagining away the reminders of reality; the effect works and the obstructions appear to disappear.

The Trance Killer Suggestion

The Trance Killer suggestion is the reversal of the Automatic Imagination process. It is, "It's just your imagination; you can stop imagining that any time you like, can't you?" This single line 'suggestion' provides the subject with the awareness that they are actually imagining the effects that they are experiencing and that they also have control over this process and can simply stop it. This line has never failed to end any AI session instantly; hands become unstuck, information that was amnesic returns, and dancing fairies vanish.We have also used the Trance Killer suggestion on hypnotic sessions set up with traditional approaches (induction and suggestions). Again, it has yet to fail, ending any supposed trance or state the subject was in and cancelling all suggestions. We're not convinced that it is necessarily a good way to end a traditional "Sleep" hypnotic session, particularly if it involved long periods of time "in trance". We are concerned that there could be physiological changes that result from imagining that you are asleep for 45 minutes that the suggestion to "Wake Up!" helps to reverse. While the trance killer will end the suggestions and session, the subject might benefit from the positive, energetic suggestions that a traditional wake-up process provides.

In terms of versatility, the trance killer can be delivered by someone other than the hypnotist, ending any ideas that an exclusive hypnotic relationship exists between the hypnotist and subject. So far, we only know of hypnotists delivering this line; when we deliver it, we give it with all the directness and authority we can muster. I have, however, sung this line, across a busy and noisy hotel bar in the trendy East End, as I was walking away from the subject, who was in the middle of a session with Marcus - it still worked.

We think that this implies that traditional hypnosis may actually be a social construct that causes the cognitive processes of automatic imagination. We think that when a subject takes a suggestion, they are actually imagining the goal of the suggestion and also imagining that this process will happen automatically. If they have been commanded to "Sleep!" then we think that they are imagining that they are asleep; if it was suggested that they "go into a trance" then we think that they are imagining that they are in a trance. Accordingly, we can see how the subject's expectations interact with their success at imagining the effects of the suggestions; if they can literally imagine it happening then the suggestion can work, otherwise, it will not. We can also see how modification of suggestibility fits in; it is simply a case of teaching the subject how to interpret the suggestions so that they automatically do the right things when hypnotised, rather than nothing or the wrong things.

The trance killer suggestion was so named, not only because it ends hypnotic sessions, but because for us, it ultimately killed any notion of trance as a special state or special process. Even calling it a suggestion is an ironic statement. If, as was suggested by Barry Thain at change | phenomena, the hypnotism conference, 2012, that the trance killer may just be another suggestion (on the premise that a special process or hypnotic state exists and that hypnosis relies upon it), then that too would kill, for us at least, the notion of trance as a special state or special process, as I'll attempt to explain.

If hypnosis relied on a special process, state or trance that was initiated with an induction and ended with an enduction (wake-up), within which hypnotic suggestions could be given, and we are to assume that the subject interprets the trance killer as a suggestion to reframe the entire hypnotic session as just an exercise in everyday imagination that they can stop at will, then at the very least we would either need to conclude that the special process, state or trance is very flaky indeed (if it could be ended so effortlessly), challenging the notion of focused attention, hypnotic relationship, and depth, or that the subject remains within the state - with the suggestion that all suggestions, including that of being in the state, are cancelled - but now without any awareness that they are still in the state, confusing it with the everyday "normal" non-hypnotic state.

The idea that the subjects are still hypnotised is questionable (if the state can be indistinguishable from the normal state, then how much of a state is it?), leaving us to conclude that the trance killer is an enduction at the very least. As an enduction, it's wording is interesting and rare in that it doesn't mention "waking up". We fail to see how an automatic, physiological special process could be ended with a simple instruction about imagination, unless this physiological process was itself the result of automatic imagination. As such, we think the trance killer kills trance, which ever way you look at it - unless you happen to already accept that trance is the effect of suggestion, rather than a requirement of hypnosis within which suggestions can be taken.

In summary, we think the effect that the trance killer suggestion has on traditional hypnosis, implies that traditional hypnosis is actually an oblique form of automatic imagination. By stripping away the rituals and replacing the suggestions with instructions to imagine, we think we can create genuine hypnotic phenomena in more subjects and get more hypnotic phenomena out of each subject.

Results to Date

At the time of writing (June 2012), we have tested the Automatic Imagination Model on about 200 subjects in informal situations, many of which were in performance or training. Excusing our confirmation bias, we are finding that 95% of self-selecting subjects can achieve a physical challenge suggestion, such as a stuck hand, and 90% can achieve amnesia. Traditionally, we would expect those figures to be closer to 52% and 23% (Kirsch et al, 1995).We ran an informal study in 2011 where we attempted to develop a standardised approach that could be used in experimentation. We tested AI with 23 subjects and found that 19 of them (83%) achieved the physical challenge suggestion but only 6 (26%) achieved the amnesia suggestion. All of these 6, however, were in the final group of 8 that received a modified version of the process that included a component to increase levels of emotion prior to the amnesia suggestion. In fairness, this small informal study was not about producing reliable results, but was more about developing the process so that it could be given in a standardised form and still achieve the results that we were seeing informally outside the lab.

We intend to take the final version of the process and test it along side suggestions from the SHSS:C on randomised groups of volunteer subjects. Developing this experiment has taken far more time and effort than we originally anticipated, but we now feel that we will soon be in a position to run a formal trial.

In Closing

Even if our informal results turn out to be skewed by confirmation bias and poor experimental design, and that in fact AI is no more powerful than traditional approaches to hypnosis, our ridiculous insight on a car journey will still have resulted in a no-induction method of hypnosis that works with those subjects that don't respond to the traditional approaches; and it will still have left us with the trance killer suggestion that appears to allow us to end any hypnotic session.If, on the other hand, it turns out (as we hope) that AI is much more powerful than traditional approaches, then we hope that all hypnotists will take an interest and that, together, we can hypnotise many more people to dance like Beyonce.

I hope you have enjoyed reading these articles, that they were easily understandable, and that you don't think I've wasted your time with needless detail. At Head Hacking, we're passionate about hypnosis and at Head Hacking Research, we're passionate about knowing how it works. Even if we're barking up entirely the wrong tree, we've certainly enjoyed the journey and feel that we now know more about hypnosis than we did when we started. I hope you feel the same way.

Please check out our training courses at headhacking.com/training and follow us on Twitter @headhackinglive. The Ripped Apart Audio CD, that explains our journey to developing the Automatic Imagination Model, is available at headhacking.com/products - it's a bargain!

Head Hacking has closed it's doors but many of the products are still available at Anthony Jacquin's website.

Kev Sheldrake, Hypnotist

Head Hacking

References

- Barry Thain, mindsci-clinic.com

- Human Givens, hgi.org.uk

- 1890, James, W, Principles of psychology (Vols. 1-2). New York: Holt

- 1946, Arnold, M. B, On the mechanism of suggestion and hypnosis

- 1995, Irving Kirsch, Christopher E. Silva, Gail Comey and Steven Reed, A spectral analysis of cognitive and personality variables in hypnosis: Empirical disconfirmation of the two-factor model of hypnotic responding

- 1997, Irving Kirsch and Stephen Jay Lynn, Hypnotic involuntariness and the automaticity of everyday life

- 1999, Gail Comey & Irving Kirsch, Intentional and spontaneous imagery in hypnosis: The phenomenology of hypnotic responding

- 2006, Amir Raz, Irving Kirsch, Jessica Pollard, and Yael Nitkin-Kaner, Suggestion Reduces the Stroop Effect

- 2008, John F. Kihlstrom, The domain of hypnosis, revisited (in Nash and Barnier, Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis)

- 2008, Amanda J. Barnier, Zoltan Dienes & Chris J. Mitchell, How hypnosis happens: new cognitive theories of hypnotic responding (in Nash and Barnier, Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis)

- 2008, Matthew G. Whalley and Gabby B. Brooks, Enhancement of suggestibility and imaginative ability with nitrous oxide

- 2011, Florin Dolcos, Alexandru D. Iordan and Sanda Dolcos, Neural correlates of emotion-cognition interactions: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations